Select one or more regions of interest

by clicking on the filter elements

Drag the filter elements horizontally,

and select one or multiple

thematic areas of interest.

The Benefits of Cover Crops

Europe

All Zones

Benefits of the practice

- Soil health

- Climate mitigation

- Water adaptation

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Cover crops improve soil quality and boost agricultural productivity. They are often planted during fallow periods, like winter or post-harvest, to prevent bare soil and reduce erosion. Cover crops offer numerous benefits for soil and climate.

They enrich soil with nutrients like nitrogen, add organic matter, and enhance soil structure. This improves water retention, making soil more resilient to drought and heavy rainfall. Cover crops also suppress weeds by covering the soil and competing with unwanted plants, reducing the need for herbicides.

Another key advantage is erosion prevention. Cover crop roots anchor soil, preventing erosion, especially on slopes or areas prone to wind and water erosion. By reducing erosion, they help maintain long-term soil fertility.

Cover crops promote biodiversity by attracting pollinators and pest predators, reducing pesticide reliance, and supporting a healthier ecosystem.

They also aid in climate mitigation and adaptation. By sequestering carbon in the soil, they reduce CO₂ levels and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, they fix nitrogen, reducing nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas.

Healthier soil with more organic matter retains water better, helping farms withstand extreme weather. This reduces the impact of droughts and floods on agricultural productivity and contributes to long-term sustainable food production.

Different cover crops serve specific needs. Clover fixes nitrogen and improves soil structure, buckwheat grows quickly and suppresses weeds, winter rye enhances weed control and soil structure, phacelia attracts pollinators, and mustard reduces soil diseases while boosting biodiversity.

Groenbemesters zijn gewassen die worden geplant om de bodemkwaliteit te verbeteren en de landbouwproductiviteit te verhogen. Ze worden vaak gebruikt tijdens braakliggende periodes, zoals in de winter of aan het einde van het groeiseizoen, om te voorkomen dat de grond leeg blijft en erosie plaatsvindt1. Groenbemesters bieden tal van voordelen voor zowel de bodem als het klimaat.

Groenbemesters verrijken de bodem met voedingsstoffen, zoals stikstof, wat essentieel is voor de groei van gewassen. Ze kunnen ook organisch materiaal toevoegen aan de bodem, wat de bodemstructuur verbetert. Dit helpt bij het verbeteren van de waterretentiecapaciteit van de bodem, waardoor de bodem beter bestand is tegen droogte en extreme regenval. Bovendien kunnen groenbemesters de groei van onkruid onderdrukken door de bodem te bedekken en de competitie aan te gaan met ongewenste planten. Dit vermindert de noodzaak voor chemische onkruidbestrijdingsmiddelen, wat gunstig is voor het klimaat.

Een ander belangrijk voordeel van groenbemesters is dat ze bodemerosie helpen voorkomen. Het wortelstelsel van groenbemesters houdt de bodem stevig op zijn plaats, waardoor erosie wordt voorkomen1. Dit is vooral belangrijk in gebieden met hellingen of waar de bodem gevoelig is voor erosie door wind of water. Door erosie te verminderen, helpen groenbemesters ook bij het behoud van de bodemvruchtbaarheid op de lange termijn.

Groenbemesters bevorderen ook de biodiversiteit. Het planten van verschillende soorten groenbemesters kan gunstig zijn voor bestuivende insecten en het aantrekken van natuurlijke vijanden van plagen. Dit kan helpen bij het verminderen van de afhankelijkheid van chemische bestrijdingsmiddelen en het bevorderen van een gezonder ecosysteem.

Wat betreft de voordelen voor het klimaat, spelen groenbemesters een cruciale rol in zowel klimaatmitigatie als klimaatadaptatie. Door koolstof vast te leggen in de bodem, helpen groenbemesters bij het verminderen van de hoeveelheid koolstofdioxide (CO₂) in de atmosfeer. Dit draagt bij aan de vermindering van de broeikasgasemissies en helpt bij het bestrijden van klimaatverandering. Bovendien kunnen groenbemesters stikstof binden, wat de uitstoot van lachgas, een krachtig broeikasgas, vermindert.

Groenbemesters dragen ook bij aan klimaatadaptatie door de bodemgezondheid te verbeteren. Een gezondere bodem met meer organisch materiaal en een beter bodemleven kan meer water vasthouden, wat essentieel is voor de veranderende klimaatomstandigheden. Dit helpt bij het verminderen van de impact van extreme weersomstandigheden, zoals droogte en overstromingen, op de landbouwproductiviteit. Bovendien draagt een gezondere bodem bij aan een duurzame voedselproductie op de lange termijn.

Er zijn verschillende soorten groenbemesters die kunnen worden gebruikt, afhankelijk van de specifieke behoeften van de grond en gewassen. Enkele populaire typen groenbemesters zijn klaver, boekweit, winterrogge, phacelia en mosterd. Klaver is bijvoorbeeld bekend om zijn vermogen om stikstof te fixeren en de bodemstructuur te verbeteren, terwijl boekweit snel groeit en onkruid kan onderdrukken. Winterrogge is ideaal voor het onderdrukken van onkruid en het verbeteren van de bodemstructuur, terwijl phacelia bestuivende insecten aantrekt en de bodemstructuur verbetert. Mosterd kan schadelijke ziektes in de bodem verminderen en de biodiversiteit vergroten.

Cover crops are plants grown to improve soil quality and increase agricultural productivity. They are often used during fallow periods, such a sin winter or at the end of the growing season, to prevent the soil from remaining bare and to reduce erosion. Cover crops offer numerous benefits for both the soil and the climate.

Cover crops enrich the soil with nutrients, such as nitrogen, which is essential for plant growth. They also add organic matter to the soil, improving its structure. This enhances the soil’s water retention capacity, making it more resilient to drought and heavy rainfall. Additionally, cover crops suppress weed growth by covering the soil and competing with unwanted plants. This reduces the need for chemical herbicides, which benefits the climate.

Another key advantage of cover crops is that they help prevent soil erosion.

Their root systems hold the soil firmly in place, preventing erosion. This is especially important in areas with slopes or where the soil is prone to erosion by wind or water. By reducing erosion, cover crops also help maintain soil fertility in the long term.

Cover crops promote biodiversity. Planting different types can benefit pollinating insects and attract natural enemies of pests. This helps reduce reliance on chemical pesticides and promotes a healthier ecosystem.

Regarding climate benefits, cover crops play a crucial role in both climate mitigation and adaptation. By sequestering carbon in the soil, they help reduce the amount of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere, lowering greenhouse gas emissions and combating climate change.

Additionally, cover crops fix nitrogen, reducing nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas.

Cover crops also contribute to climate adaptation by improving soil health.

Healthier soil with more organic matter and better microbial activity retains more water, essential for changing climate conditions. This helps reduce the impact of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, on agricultural productivity. Moreover, healthier soil supports long-term sustainable food production.

Various types of cover crops can be used depending on soil and crop needs.

Popular options include clover, buckwheat, winter rye, phacelia, and mustard. Clover fixes nitrogen and improves soil structure, buckwheat grows quickly and suppresses weeds, winter rye enhances weed control and soil structure, phacelia attracts pollinators, and mustard reduces soil diseases while boosting biodiversity.

Profitable Climate Actions on Dairy Farms

Sweden

Nordic Cluster

Benefits of the practice

- Improved milk yields and feed ration

- Less feed waste

- Better growth and health of the animals

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Measures that benefit the environment and climate often improve farm economics by optimizing resource use and efficiency. Greppa Näringen conducted climate calculations using the Vera Klimatkollen tool on a dairy farm to assess the impact of different strategies on climate and economy.

The modeled farm has conventional production with:

200 cows

240 ha arable land (170 ha grassland/field pasture)

50 ha natural pasture

Grassland, cereals, and whole-crop silage (oats/peas)

Bull calves and some grain/straw sold

Feed Ration (kg DM/day)

Ley & whole-crop silage: 10.5

Beet pulp (molasses dried): 3.6

Grain: 1.7

Concentrate/protein mix: 4.3

ExPro (rapeseed protein): 1.6

Key Figures:

Milk yield: 10,000 kg ECM

Young heifers: 130 kg

Old heifers: 65 kg

Bull calf sale age: 2 weeks

Calving age: 27 months

Recruitment rate: 35%

Calf mortality: 5%

Calving interval: 13.2 months

Milk delivered: 92%

Forage waste: 15%

Alternative Scenarios

Option 2: Replaces soya/palm products with more self-produced feed, lowering the farm’s carbon footprint.

Option 3: Focuses on better animal growth, health, and management, reducing recruitment rates, calving ages, and calf mortality.

Option 4: Increases milk yield to 12,000 kg ECM per cow with improved management, using more silage but maintaining feed ratios.

Option 5: Reduces feed wastage from 15% to 5%, decreasing HP pulp purchases. The freed land is used to grow rapeseed and field beans for sale.

Options 6, 7, 8: Combine multiple strategies.

The greatest impacts come from higher milk yields, improved feed conversion, reduced feed waste, and better animal growth and health.

Åtgärder som är bra för miljön och klimatet är också ofta bra för gårdens ekonomi. Det handlar om att hushålla med resurser och vara så effektiv som möjligt i sin produktion. Greppa Näringen har gjort klimatberäkningar med verktyget Vera klimatkollen på en mjölkgård för att se vad olika alternativ har för effekt på gårdens klimatpåverkan och ekonomi.

Den mjölkgård som använts i klimatberäkningarna har konventionell drift med nedanstående produktion och nyckeltal (alternativ 1).

200 kor

240 ha åkermark (varav vall och åkerbete 170 ha)

50 ha naturbetesmark

Vall, spannmål och helsädesensilage (havre/ärt)

Tjurkalvar samt en del av spannmålen och halmen säljs

I alternativ 2 är soja- och palmprodukter utbytta mot mer egenproducerat foder som ger lägre klimatavtryck. De inköpta fodermedlen är totalt sett lägre då mer ensilage och spannmål ges till korna.

I alternativ 3 är bättre tillväxt, hälsa och skötsel i fokus. Detta ger lägre rekryteringsprocent, inkalvningsålder och kalvdödlighet.

I alternativ 4 med högre mjölkavkastning genom bättre management. höjs produktionen till 12 000 kg ECM per ko och år. Korna äter mer ensilage, men i övrigt är foderstaten och nyckeltalen oförändrade.

Alternativ 5 med minskning av foderspill och överutfodring av grovfoder och HP-massa, från 15 % till 5 %. Gården köper in mindre HP-massa och odlar mindre ensilage och helsäd. På den åkermarken odlas i stället raps och åkerbönor till avsalu.

Alternativ 6, 7 och 8 kombinerar flera scenario. Modelleringen visar att störst betydelse har förbättrad mjölkavkastning och foderstat, mindre foderspill samt bättre tillväxt och hälsa hos djuren.

In Sweden, two different tools, Vera Klimatkollen and Agrosfär, are used to perform climate calculations within Climate Farm Demo. Greppa Näringen, the developer of Vera Klimatkollen, has modeled several scenarios for a dairy farm to determine whether measures that benefit the climate are also economically advantageous for the farm.

The dairy farm used in the modeling has conventional farming with the following production and key figures (Option 1):

• 200 cows

• 240 ha arable land (of which 170 ha is grassland and field pasture)

• 50 ha natural pasture

• Grassland, cereals, and whole-crop silage (oats/peas)

• Bull calves and part of the grain and straw sold

Key Figures and Feed Ration (kg DM/day)

• Milk production: 10,000 kg ECM

• Ley & whole-crop silage: 10.5

• Beet pulp (molasses dried): 3.6

• Grain: 1.7

• Concentrate & protein mix: 4.3

• ExPro (rapeseed protein): 1.6

• Young heifers: 130 kg

• Old heifers: 65 kg

• Bull calf sale age: 2 weeks

• Calving age: 27 months

• Recruitment rate: 35%

• Calf mortality: 5%

• Calving interval: 13.2 months

• Milk delivered: 92%

• Forage wastage: 15%

Alternative Scenarios (see Table 1)

– Option 2: Replaces soya and palm products with more self-produced feed, which has a lower carbon footprint. The overall quantity of purchased feed is reduced as cows receive more silage and cereals.

More ley is grown, while less oats and spring wheat are cultivated. The feed ration is formulated to maintain the same milk yield as the baseline. The economic outcome remains almost unchanged, meaning that production and profitability are maintained, but with a significantly lower climate impact.

– Option 3: Focuses on improved growth, health, and management, leading to lower recruitment rates, reduced calving ages, and lower calf mortality. To distinguish between the climate footprint of replacement heifers and slaughter animals, the farm sells all heifer calves that are not recruited. This results in 75 younger heifers and 45older heifers, reducing the recruitment rate to 30%, calving age to 24months, and calf mortality to 2%. Fewer animals go to carcass and slaughter since future slaughter heifers are sold at a younger age.

While income from slaughtering animals decreases, savings are made on feed, buildings, and labor. If the farm has limited space for young animals, selling more animals earlier can be beneficial. More straw and silage are also sold.

– Option 4: Increases milk yield to 12,000 kg ECM per cow per year through better management. Cows consume more silage, but the feed ration and key figures remain unchanged. The farm grows 112tonnes (t) more forage, while producing 30 t less winter wheat and 30t less spring wheat compared to the baseline. Since more forage is grown and more cereals are retained, total income decreases, but increased milk income compensates for this.

– Option 5: Reduces feed wastage and overfeeding of forage and beet pulp from 15% to 5%. The farm purchases 40 t less beet pulp and cultivates 127 t less silage and 12 t less whole-crop silage. Instead, 21 t of rapeseed and 22 t of field beans are grown on the freed-up arable land for sale, generating an additional SEK 127,000. Reducing input losses also lowers the farm’s carbon footprint on the final products.

– Options 6, 7, and 8: Combine multiple scenarios. The most significant impacts result from improved milk yields, better feed conversion, reduced feed waste, and enhanced animal growth and health.

Green Manure: Environmental Measure for Sustainable Fruit Production

Italy

Mediterranean Area

Benefits of the practice

- Farm production efficiency

- Environmental sustainability

- Mitigation strategies

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Among the agronomic practices used to increase fertility, improve soil structure, enhance biodiversity and reduce the environmental impact of agricultural systems, green manure plays a key role. It is referred to as green manure because it can replace animal waste in the organic fertilization of cultivated land. This practice is widely used in horticulture to counteract the deterioration of soil fertility.

Green manure involves sowing specific intercalary herbaceous plants in rotation with high-income crops. The goal is to bury these plants to improve the productive performance of the next horticultural crop, orchard, or vineyard. However, its primary function is to increase organic matter in the soil by incorporating the plant mass, with all the resulting benefits.

The maximum benefit of this practice is achieved by using legumes, grasses, or buckwheat, which effectively absorb nitrogen. Ideal seed mixtures should have biological cycles of similar duration to ensure uniform flowering. Additionally, mixtures with coarse shredding should be used, with residues left to dry in the field before burial, maximizing the organic matter contribution to the soil.

Following these simple guidelines, combined with careful planning, allows farms to add large quantities of high-quality organic material to the soil. This enriches the soil with key biological fertility factors, benefiting farms by providing a more productive substrate.

A carefully chosen green manure composition also helps prepare a more favorable growing environment for the next crop, ensuring better agricultural results.

Fra le pratiche agronomiche usate per aumentare la fertilità, migliorare la struttura del suolo, migliorare la biodiversità e diminuire l’impatto ambientale dei sistemi agricoli c’è il sovescio che viene definito come letame verde, perché può, appunto, sostituire le deiezioni animali nella concimazione organica dei terreni coltivati. Questa pratica agronomica viene utilizzata nell’orticoltura per contrastare il deteriorarsi della fertilità. Il sovescio è una tecnica che consiste nella semina di specifiche erbacee intercalari in rotazione con colture ad alto reddito. Lo scopo è quello di interrare le intercalari e migliorare così le performance produttive della coltura orticola successiva in rotazione oppure di un frutteto o di un vigneto. La funzione fondamentale del sovescio è comunque l’aumento di sostanza organica nel suolo, conseguente all’interramento della massa vegetale, con tutti i benefici che ne derivano. La massima utilità di questa pratica si ottiene utilizzando leguminose, graminacee o grano saraceno che assorbono azoto; miscugli che abbiano cicli biologici di durata molto simile in modo tale da avere una fioritura omogenea, miscugli che abbiano una trinciatura grossolana i cui residui siano lasciati essiccare in campo prima dell’interramento in modo tale da apportare una levata quantità di sostanza organica nel terreno. L’osservazione di queste semplici “regole” unita ad una precisa programmazione permette alle aziende di apportare la terreno grandi quantità di sostanza organica di qualità elevata. Il terreno così si arricchisce di tutti quei fattori che ne vanno a comporre la fertilità biologica a tutto vantaggio delle aziende che possono disporre di un substrato su cui produrre con migliori risultati. La scelta oculata della composizione del sovescio consente poi di preparare, già in questa fase, un substrato più “accogliente” per la coltura che lo seguirà.

Among the agronomic practices used to increase fertility, improve soil structure, enhance biodiversity, and reduce the environmental impact of agricultural systems, green manure plays a key role. It is called green manure because it can replace animal waste in the organic fertilization of cultivated land. This practice is used not only on conventional and organic farms but is also widely adopted in fruit-producing farms to counteract soil fertility loss.

Green manure involves alternating normal crops with specific plant families that have particular characteristics. These plants are chopped and buried, enriching soil fertility. This technique allows for a significant increase in organic matter when manure is not available.

The benefits of green manure include:

• Better nitrogen management: Root nodules, especially those of legumes, fix atmospheric nitrogen (N₂), making it directly available to plants.

• Improved soil structure: Makes the soil softer and more workable while increasing water and nutrient retention.

• Erosion prevention: Enhances structural stability and protects against erosion and weathering, thanks to the surface layer of plant sand the root system in the subsoil.

• Natural pest control: Green manure crops act as natural pesticides by releasing biocidal molecules (biofumigation) from their roots, unlike intensive agriculture, which relies on chemical pesticides that release ammonia into the air.

• Weed suppression: Helps control weed growth by competing for resources.

• Aesthetic and ecological benefits: During flowering, mixed-species sowing creates colorful landscapes, while honey-producing plants attract beneficial insects such as bees.

The most used green manure plants belong to these categories:

• Legumes (clover, vetch, broad bean, sainfoin, protein pea) provide nitrogen through root symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

• Grasses (barley, rye, oats, fescue) and buckwheat help absorb nitrogen from the soil.

A good green manure practice involves selecting varieties with similar biological cycles to ensure uniform flowering. Proper shredding and drying of residues before burial maximizes the organic matter supply, which also depends on the carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio.

Following these simple principles, combined with precise planning, allows farms to enrich the soil with large quantities of high-quality organic matter. This enhances biological fertility, providing farmers with a more productive substrate for future crops. The careful selection of green manure composition ensures that the soil is well-prepared for the next crop, creating a more favorable growing environment right from the start.

Fat Supplementation of Dairy Cow Diets

Latvia

Temperate, Humid Continental

Benefits of the practice

- Feed enrichment

- Reduction of methane emissions

- Fats in dairy cow diets

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Fat enrichment involves increasing the proportion of certain feed ingredients—such as fatty substances (rapeseed, linseed, sunflower oil, rapeseed oil)—to 5–6% of dry matter in the feed. The primary effect of fat supplementation is to replace other energy sources, mainly carbohydrates, and to reduce methane production.

Scientific studies on sheep, cattle, and dairy cows in other countries (Beauchemin et al., 2008) have shown that for every 1% increase in fat (on a dry matter basis), CH₄ emissions decrease by 2.2–7.3%:

⦁ Coconut oil: 7.3% reduction

⦁ Soybean and sunflower oil: 4.1% reduction

⦁ Linseed oil: 4.8% reduction

⦁ Rapeseed oil: 2.5% reduction

⦁ Fats (saturated): 3.5% reduction

By formulating feed rations for dairy cows, it is evident that including rapeseed or rapeseed oil can reduce methane emissions by approximately 9%. This approach is a viable option not only for conventional farms but also for organic farms.

Reducing microbial activity in the rumen lowers fiber digestion and alters volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiles—acetic (60–70%), propionic (20–25%), and butyric acid (10–15%). Imbalances affect milk fat/protein and methane emissions. The acetic-to-propionic acid ratio influences hydrogen use for methane production; typical ratios range from 9:1 to 4:1. Proper feed composition can reduce methane losses. Studies show 5% dietary fat improves early lactation milk yield, with cows able to utilize 0.45 g/day of added fat. Grain-based diets with fat maintain energy and fiber intake. Supplementing up to 5% fat is effective, especially in large herds grouped by lactation phase. Fat enrichment reduces CH₄ emissions—1% more fat lowers emissions by 5%. Feed modeling shows rapeseed oil reduces methane by ~9%, offering a promising strategy for both organic and conventional farms to cut GHG emissions while maintaining productivity.

Barības bagātināšana ar taukvielām pamatojas uz atsevišķu barības sastāvdaļu, t.i. taukvielu (rapšu sēklas, linsēklas, saulespuķu eļļa, rapša eļļas), īpatsvara palielināšanu barībā 5 līdz 6% apmērā no sausnas. Galvenā tauku ietekme izpaužas tā, ka ar taukiem barībā aizvieto citus enerģijas avotus, pamatā ogļhidrātus un samazina metāna veidošanos.

Zinātnieku pētījumos citās valstīs ar aitām, liellopiem un slaucamām govīm (Beauchemin et al., 2008), noskaidrots, ka katrs 1% tauku (uz sausni), samazina CH4 emisiju par 2,2–7,3% apmērā:

⦁ kokosriekstu eļļa par 7,3%;

⦁ sojas un saulespuķu eļļa par 4,1%;

⦁ linsēklu eļļa par 4,8%;

⦁ rapšu eļļa par 2,5%;

⦁ tauki ( piesātinātās taukskābes) par 3,5%.

Sastādot barības devas (sk.1.attēlu) slaucamajām govīm, redzams, ka metāna emisiju samazinājumu par ~9% varam panākt iekļaujot rapšu sēklas vai rapšu eļļu, kas ir reāls risinājums ne tikai konvencionālajās, bet arī bioloģiskajās saimniecībās.

Samazinot mikrobu aktivitāti spureklī, samazinās kokšķiedras sagremošana un mainās gaistošo taukskābju (VFA) – etiķskābes (60-70 %), propionskābes (20-25 %) un sviestskābes (10-15 %) – profils. Disbalanss ietekmē piena tauku/proteīnu un metāna emisiju. Etiķskābes un propionskābes attiecība ietekmē ūdeņraža izmantošanu metāna ražošanai; tipiskā attiecība ir no 9:1 līdz 4:1. Pareizs barības sastāvs var samazināt metāna zudumus. Pētījumi liecina, ka 5 % tauku daudzums barības devā uzlabo izslaukumu laktācijas sākumā, un govis var izmantot 0,45 g pievienoto tauku dienā. Uz graudiem balstītas barības devas ar taukiem saglabā enerģijas un kokšķiedras uzņemšanu. Tauku piedevas līdz 5 % ir efektīvas, jo īpaši lielos ganāmpulkos, kas sagrupēti pēc laktācijas fāzes. Tauku pievienošana samazina CH₄ emisijas – par 5% vairāk tauku samazina emisijas par 5%. Barības devu modelēšana liecina, ka rapšu eļļa samazina metānu par ~9%, piedāvājot daudzsološu stratēģiju gan bioloģiskajām, gan tradicionālajām saimniecībām, lai samazinātu SEG emisijas, vienlaikus saglabājot produktivitāti.

Fat enrichment involves increasing the proportion of certain feed ingredients, specifically fatty substances (rapeseed, linseed, sunflower oil, rapeseed oil), to 5–6% of dry matter in the feed. The primary effect of fat supplementation is to replace other energy sources, mainly carbohydrates, and to reduce methane production.

Research by international scientists has explored various strategies to reduce methane emissions from the intestinal tract of cattle, with one proposed solution being fat enrichment in feed through the inclusion of fatty acids.

Fat enrichment involves increasing the proportion of fatty acids in the diet by incorporating various vegetable oils (e.g., sunflower, rapeseed, linseed, hemp, cottonseed). Animal nutrition scientists in Latvia recommend adding vegetable oils to compound or complete mixed rations (TMR) at 5% of dry matter for dairy cows, pregnant heifers, breeding heifers, young stock (6–12months), and calves (3–6 months), and 3% for fattening and beef cattle(Latvian, 1991, 1998, 2013; Ositis, 2000).

Scientific studies on sheep, cattle, and dairy cows (Beauchemin et al., 2008)indicate that every 1% increase in fat (on a dry matter basis) reduces CH₄ emissions by 2.2–7.3%:

• Coconut oil: 7.3% reduction

• Soybean and sunflower oil: 4.1% reduction

• Linseed oil: 4.8% reduction

• Rapeseed oil: 2.5% reduction

• Saturated fats: 3.5% reduction

Fat supplementation partially replaces carbohydrates, which are fermented in the rumen, producing CH₄ as a by-product. In contrast, fat is processed in the intestine, where methane is not generated. Additionally, unsaturated fatty acids found in linseed, rapeseed, and sunflower seeds selectively inhibit certain microorganisms in the rumen, reducing their activity and there by lowering CH₄ emissions.

The reduction in microbial activity (infusoria, yeast fungi, bacteria) in the rumen decreases fiber digestion (cellulose, hemicellulose), impacting the formation of volatile fatty acids (VFAs):

• Acetic acid: 60–70%

• Propionic acid: 20–25%

• Butyric acid: 10–15%

An imbalance in these VFAs affects production, metabolism, and milk composition, as milk fat and protein content can decrease rapidly (Latvian,1991). The rumen fermentation mechanism regulates hydrogen availability for methane production. The acetic-to-propionic acid ratio is a key factor:

• If the ratio is 5:1, methane energy loss is 0%.

• If all carbohydrates ferment into acetic acid without propionic acid production, methane energy loss can reach 33%.

• Typical acetic-to-propionic acid ratios range from 9:1 to 4:1(Johnson and Johnson, 1995).

Since the formation of VFAs is influenced by feed composition, proper diet formulation plays a crucial role in methane reduction strategies.

Impact on Milk Production and GHG Emissions

Long-term studies indicate that 5% fat in total dry matter optimizes milk production in early lactation (Palmquist, 1983). In addition to naturally occurring fats, cows can utilize an additional 0.45 g/day of fat (Palmquist,1983).

The most accessible energy source for dairy cows is grain. Adding fat to starchy, grain-based diets maintains high energy levels while allowing for adequate fiber intake (Palmquist and Conrad, 1980). Fat supplementation up to 5% of dry matter at the start of lactation helps address energy deficits without negatively impacting metabolism and production. This strategy is particularly effective on farms grouping cows by lactation phase, especially in herds with more than 50 cows (Project report: “Development of a methodology for estimation of GHG emissions from the agricultural sector and data analysis with modeling tools integrating climate change” Contract No 2014/94).

Impact of Fat Enrichment on GHG Emissions

Studies have shown that increasing dietary fat by 1% reduces CH₄ emissions by 5% (Grainger, Beauchemin, 2011). Feed ration modeling (see Figure 1)suggests that incorporating rapeseed or rapeseed oil can lower methane emissions by ~9%, making it a viable solution for both conventional and organic farms.

Dairy Cow Feed Rations and Ammonia Emissions

Latvia

Temperate, Humid Continental

Benefits of the practice

- Reducing nitrogen losses

- Balancing feed rations

- Ammonia emissions

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

On farms, reducing nitrogen losses in livestock not only helps to preserve the environment, but also improves the farm’s bottom line.

Ruminant livestock are not very efficient at using the nitrogen they take up in feed. If rations are very precisely calculated, 30 to 35 percent of the nitrogen in feed proteins and non-protein compounds becomes a component of milk. The rest of the nitrogen is excreted from the body mainly in urine and faeces. About 60 to 80 per cent of urinary nitrogen is in the form of urea.

Urea concentration in urine is an important indicator of ammonia emissions in dairy farming. It is possible to adjust both the urine output, the urinary urea concentration and the total manure output with the feed ration. It must be clearly understood that urine and faeces separately emit very minimal quantities of ammonia, but only after they reach the floor surfaces in the housing and these two fractions of excreta physically mix, ammonia is released.

There are additional factors that influence the evaporation of ammonia in cow housing. These include temperature, air velocity, pH, size of floor surfaces, moisture content of manure and storage time. For example, high pH and temperature contribute to increased ammonia emissions. Dairy cow manure typically has a pH between 7.0 and 8.5, which allows ammonia to be released into the atmosphere quite quickly.

The deposition of atmospheric ammonia and chemical compounds resulting from atmospheric chemical reactions with ammonia (i.e. ammonium aerosol) is thought to contribute to water and soil acidification and eutrophication.

Thus, one solution is to balance feed rations as closely as possible to the amino acid needs of the cow: the amount of crude protein in the diets of high-yielding cows can be safely reduced, allowing farms to maintain high milk yields (above 35 kg per cow per day) while improving nitrogen use efficiency.

Saimniecībās, samazinot slāpekļa zudumus ganāmpulkā, palīdzam ne tikai vides saglabāšanai, bet arī uzlabojam saimniecības peļņas rādītājus.

Atgremotāji ne īpaši efektīvi izmanto ar barību uzņemto slāpekli. Ja barības devas ir ļoti precīzi sarēķinātas, tad 30 līdz 35 procenti no slāpekļa, kas ir barības olbaltumvielu sastāvā un neproteīna savienojumos, kļūst par piena sastāvdaļu. Pārējais slāpeklis no organisma tiek izvadīts pamatā ar urīnu un fēcēm. Apmēram 60 līdz 80 procenti no urīna slāpekļa ir urīnvielas formā.

Urīnvielas koncentrācija urīnā ir būtisks indikatorrādītājs amonjaka emisijām piena lopkopībā. Ar barības devām ir iespējams koriģēt gan urīna daudzumu, gan urīnvielas koncentrāciju urīnā, gan kopējo mēslu daudzumu. Ir pilnīgi skaidri jāsaprot, ka urīns un fēces atsevišķi emitē ļoti minimālus amonjaka daudzumus, bet tikai pēc nonākšanas uz grīdu virsmām novietnēs un abām šīm izdalījumu frakcijām fiziski sajaucoties notiek amonjaka izdalīšanās.

Ir arī papildu faktori, kas ietekmē amonjaka iztvaikošanu govju novietnēs. Tie ir temperatūra, gaisa plūsmas ātrums, pH, grīdas virsmu laukumu lielums, kūtsmēslu mitruma saturs un uzglabāšanas laiks. Piemēram, augsts pH un temperatūra veicina paaugstinātu amonjaka emisiju. Slaucamo govju kūtsmēslu pH parasti svārstās no 7,0 līdz 8,5, kas ļauj amonjakam diezgan ātri izdalīties atmosfērā.

Tiek uzskatīts, ka atmosfēras amonjaka un ķīmisko savienojumu nogulsnēšanās, kas rodas atmosfēras ķīmiskās reakcijās ar amonjaku (t.i., amonija aerosolu), veicina ūdens un augsnes paskābināšanos un eitrofikāciju. 1. attēlā parādīts slāpekļa cikls un ietekme gan uz ūdens, gan gaisa kvalitāti.

On farms, reducing nitrogen losses in livestock not only helps to preserve the environment but also improves the farm’s bottom line.

Ruminant livestock are not very efficient at using the nitrogen they take up in feed. If rations are very precisely calculated, 30 to 35 percent of the nitrogen in feed proteins and non-protein compounds becomes a component of milk. The rest of the nitrogen is excreted from the body, mainly in urine and faeces. About 60 to 80 percent of urinary nitrogen is in the form of urea.

Urea concentration in urine is an important indicator of ammonia emissions in dairy farming. It is possible to adjust both urine output, urinary urea concentration, and total manure output with the feed ration. It must be clearly understood that urine and faeces separately emit very minimal quantities of ammonia, but only after they reach the floor surfaces in housing and these two fractions of excreta physically mix is ammonia released.

There are additional factors that influence the evaporation of ammonia in cow housing. These include temperature, air velocity, pH, size of floor surfaces, moisture content of manure, and storage time. For example, high pH and temperature contribute to increased ammonia emissions.

Dairy cow manure typically has a pH between 7.0 and 8.5, which allows ammonia to be released into the atmosphere quite quickly.

The deposition of atmospheric ammonia and chemical compounds resulting from atmospheric chemical reactions with ammonia (i.e. ammonium aerosol) is thought to contribute to water and soil acidification and eutrophication. Figure 1 shows the nitrogen cycle and its impact on both water and air quality.

There are two ways to reduce nitrogen losses from cows. First, the microorganisms living in the rumen must effectively “consume” the protein and nitrogen present. The second is to balance feed rations as closely as possible to the amino acid needs of the cow so that the total amount of protein is reduced, and the amount of excess nitrogen is correspondingly lowered.

Feeding high-protein diets is not only harmful to the environment but also to the animals. Making the most of nitrogen in the animal is also a way to reduce the cost of milk production. If the liver is overloaded with ammonia, blood urea levels will increase, as will the amount of milk urea (MUN). This can have adverse effects on cow health and reproduction. Excessive ammonia build-up in the cow results from overfeeding, when too much nitrogen and/or protein reaches the micro-organisms in the rumen.

Additional energy is required to remove the excess nitrogen from the body, which can lead to a reduction in milk yield and other performance parameters. Excess ammonia is converted to urea in the kidneys and liver.

Urea is a small organic compound formed from carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen. It is primarily eliminated from the body in the urine, but as blood urea levels rise, so does the amount of urea in milk.

This is why the amount of urea in milk is measured—to assess how much of the protein (nitrogen) intake is being lost due to inefficient utilization.

By balancing rations according to amino acid requirements, the amount of crude protein in the diets of high-yielding cows can be safely reduced from17.5% to 16.6%, allowing farms to maintain high milk yields (above 35 kg per cow per day) while improving nitrogen use efficiency.

There is a second benefit: the amount of nitrogen in the manure is reduced, which means fewer hectares are needed for manure spreading to stay within nitrogen limits per hectare.

A very important factor in successfully reducing crude protein in the ration is accurate on-farm feeding and knowing the chemical composition of the forage very precisely—or conducting forage analyses on the farm

Pea-Rapeseed Rotation: Improving Performance and Reducing Production Costs

France

Oceanic & Continental Zones

Benefits of the practice

- Improvement of soil fertility: Nitrogen fixation by peas increases mineral soil nitrogen for rapeseed and hence reduces GHG emissions

- Improvement of rapeseed establishment and weed management

- Increased rapeseed yield by 1.9 quintals per hectare

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Feasibility trials of growing rapeseed after protein peas have demonstrated several practical advantages for farmers. Peas fix atmospheric nitrogen, enriching the soil for rapeseed, which reduces the need for nitrogen fertilizers, thereby lowering production costs and GHG emissions. Rapeseed efficiently absorbs the residual nitrogen from peas, resulting in better nutrient utilization and enhanced growth.

Peas leave minimal crop residues, facilitating rapeseed planting without plowing. This rotation improves soil preparation and reduces the risk of phytotoxicity from herbicides, compared to a wheat predecessor. Optimized seeding conditions further promote good rapeseed emergence.

Regarding weed management, cereal regrowth before rapeseed may require a specific grass herbicide, whereas pea regrowth is frost-sensitive and does not pose a major issue. The diversification of rotations with peas also improves weed control at the rotation level, thanks to staggered sowing dates and the use of different herbicide molecules.

Observations revealed no significant differences in sclerotinia levels between pea and cereal precedents, indicating that the pea-rapeseed rotation does not increase disease risk. This helps maintain good crop health without requiring additional fungicide treatments.

Trial results also show that the nitrogen fertilizer requirement for rapeseed is, on average, reduced by 19 kg N/ha after peas compared to cereals. This fertilizer saving, combined with a yield increase of 1.6 quintals per hectare, enhances the profitability of growing rapeseed after peas. Farmers can thus benefit from lower production costs, improved economic performance, and reduced GHG emissions.

Les essais de faisabilité de la culture du colza après un pois protéagineux ont montré plusieurs avantages pratiques pour les agriculteurs. Le pois fixe l’azote atmosphérique, enrichissant le sol pour le colza suivant. Cela permet de réduire les besoins en engrais azotés, diminuant ainsi les coûts de production et les émissions de gaz à effet de serre. Le colza valorise bien l’azote résiduel du pois, ce qui se traduit par une meilleure utilisation des ressources en nutriments et une croissance accrue.

Le pois laisse peu de résidus de culture, facilitant l’implantation du colza sans labour. Cette rotation permet une meilleure préparation du sol et réduit les risques de phytotoxicité par rapport à une culture précédente de blé. Les conditions de semis sont ainsi optimisées, favorisant une bonne levée du colza.

En termes de gestion des adventices, les repousses de céréales cultivées avant le colza peuvent nécessiter l’application d’un désherbant antigraminées spécifique, tandis que les repousses de pois sont généralement gélives et ne posent pas de problème majeur. La diversification de la rotation avec le pois permet également de mieux gérer l’enherbement à l’échelle de la rotation, grâce à un décalage des dates de semis et à l’utilisation de différentes molécules herbicides.

Les observations n’ont pas révélé de différence significative dans les niveaux d’attaque de sclérotinia entre les précédents pois et céréales, indiquant que la succession pois-colza n’augmente pas le risque de cette maladie. Cela permet de maintenir une bonne santé des cultures sans nécessiter de traitements fongicides supplémentaires.

Les résultats des essais montrent également que la dose d’engrais azoté nécessaire pour le colza est en moyenne réduite de 19 kg N/ha après un pois par rapport à une céréale à paille. Cette économie d’engrais, combinée à l’augmentation du rendement de 1.6 quintaux par hectare, contribue à améliorer la rentabilité de la culture du colza après un pois. Les agriculteurs peuvent ainsi bénéficier d’une réduction des coûts de production, d’une meilleure performance économique et d’une diminution de leurs émissions de gaz à effet de serre.

Feasibility trials of growing rapeseed after peas have demonstrated several practical advantages for farmers. Peas are legume crops that fix atmospheric nitrogen through symbiotic bacteria, increasing soil mineral nitrogen content and benefiting subsequent crops such as rapeseed. As a result, the need for nitrogen fertilizers is reduced, lowering production costs and GHG emissions. Rapeseed efficiently absorbs residual nitrogen from peas, improving nutrient utilization and promoting better growth. Trial shave shown that the nitrogen fertilizer requirement for rapeseed is, on average, reduced by 19 kg N/ha after peas compared to cereals, while also achieving higher seed yields.

Peas leave fewer crop residues, facilitating rapeseed planting without plowing. This rotation enhances soil preparation and reduces the risk of phytotoxicity from herbicides, compared to a wheat predecessor.

Optimized seeding conditions further support good rapeseed emergence.

Experiments have shown that rapeseed grown after peas produces 1.6 quintals more per hectare than rapeseed following cereals. This yield increases results from better nitrogen utilization and more favorable seeding conditions.

Regarding weed management, cereal regrowth before rapeseed may require a specific grass herbicide, whereas pea regrowth is frost-sensitive and does not pose a major issue. Crop diversification with peas improves weed control at the rotation level due to staggered sowing dates and the use of different herbicide molecules. Observations indicate that the pea rapeseed rotation reduces weed pressure, particularly from grasses, and limits herbicide interventions, contributing to more sustainable crop management.

Sclerotinia, a common pathogen affecting both crops, does not pose a higher risk when rapeseed follows peas instead of cereals. This ensures good crop health without requiring additional fungicide treatments, reducing costs and environmental impacts associated with phytosanitary products.

The trial results confirm that fertilizer savings, combined with increased yields, improve the profitability of growing rapeseed after peas. Farmers benefit from lower production costs, better economic performance, and reduced GHG emissions.

In conclusion, the pea-rapeseed rotation offers significant agronomic and economic advantages, particularly in terms of soil fertility, weed management, yield improvement, production cost reduction, and GHG emissions mitigation. These results encourage the adoption of this practice to enhance the sustainability and profitability of cropping systems.

How to Reduce the Carbon Footprint in Arable Crop Production?

Croatia

Continental and Mediterranean

Benefits of the practice

- Decrease GHG emission in arable production

- Cover crop sowing methods

- Positive effect of introducing legumes into the crop rotation

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

We have been witnessing climate change, and its impact on agriculture is enormous. Agriculture is one of the most vulnerable sectors affected by climate change. Therefore, several agricultural producers who are aware of this impact, as well as the need to adapt their production and implement climate-smart practices on their farms, have joined the Climate Farm Demo project.

It is important to present to farmers engaged in arable production the structure of sowing on farms, the method of tillage, and whether, and which, cover crops are sown (winter or spring). As integral stakeholders of the ecosystem, seed producers and distributors—with their offer of leguminous seeds and mixtures of seeds from different botanical species for various purposes—must be included in efforts to adapt agriculture to climate change.

It is also very important to show farmers different types of winter cover crops, such as mixtures of winter vetch, winter broad beans, black beans, and broad bean crops intended for processing. Demonstrating the nodules on the roots of legumes and emphasizing the positive effects of introducing legumes into crop rotation is essential.

However, it is important to emphasize that sowing cover crops involves several soil maintenance measures that include the presence of vegetation on the land, with the aim of maintaining or increasing soil organic matter content, improving the physical properties of the soil (soil structure, water-air relations), accumulating nitrogen in the soil through legume cultivation, enhancing soil microbiological activity, and controlling weeds through biological methods—in general, increasing soil fertility.

Additionally, cover crops serve the important function of “soil cover” with the intention of preventing erosion (by water and/or wind) and nutrient leaching, primarily nitrates, thereby helping to prevent groundwater pollution.

Svjedoci smo klimatskih promjena, a utjecaj klime na poljoprivredu je ogroman. Poljoprivreda je jedan od najranjivijih sektora na koje utječu klimatske promjene. Stoga su se poljoprivredni proizvođači koji su svjesni utjecaja klimatskih promjena na poljoprivrednu proizvodnju, ali i potrebe da svoju poljoprivrednu proizvodnju prilagode te implementiraju klimatski pametne prakse na svom gospodarstvu, uključili u CFD projekt. Stoga je bitno poljoprivrednicima koji se bave ratarskom proizvodnjom predstaviti strukturu sjetve na gospodarstvima, način obrade tla te siju li pokrovne usjeve i koje (ozime ili jare). Kao sastavni dionici AKIS-a, u prilagodbu na klimatske promjene u ratarstvu moraju se uključiti i proizvođači i distributeri sjemena sa svojom ponudom sjemena mahunarki, ali i smjesa sjemena različitih botaničkih vrsta za različite namjene. Također, vrlo je bitno ratarima tijekom obilaska parcela prikazati različite tipove ozimog pokrovnog usjeva poput smjese ozime grahorice, ozimog boba i inkarnatke te usjeva boba namijenjenog preradi. Svakako treba prikazati nodule na korijenu mahunarki i istaknuti pozitivan učinak uvođenja mahunarki u plodored. Međutim, bitno je naglasiti da sjetva pokrovnih usjeva podrazumijeva više različitih mjera održavanja tla uz prisutnost vegetacije na zemljištu, a s namjerom održanja ili povećanja sadržaja organske tvari tla, poboljšanja fizikalnih svojstava tla (struktura tla, vodozračni odnosi u tlu), akumulacije dušika u tlu uzgojem mahunarki (leguminoza), poboljšanja mikrobiološke aktivnosti tla, suzbijanja korova biološkim mjerama, odnosno, općenito – podizanja plodnosti tla. Pri tome pokrovni usjevi imaju dodatnu funkciju “pokrivača tla” s namjerom sprječavanja erozije (vodom i/ili vjetrom) i ispiranja hranjiva, prije svega nitrata, a time i sprječavanja onečišćenja podzemnih voda.

For the past ten or more years, we have witnessed climate change causing significant disruptions in everyday social activities. Unfortunately, alongside energy and transport as the main sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, agriculture and forestry are considered the third largest sources of GHGs in most countries.

The Republic of Croatia does not belong to the group of leading European GHG emitters, but we certainly cannot—and do not want to—remain isolated in the long-term effort to achieve zero emissions by 2050. The numerical indicators and forecast models related to climate change, which are circulating within the scientific and professional communities, are concerning in many respects. They call for serious and urgent changes in our way of thinking, living, eating, transporting, supplying energy, managing waste, and making interventions in agriculture and forestry.

The agricultural sector, in particular, will face major challenges in adapting to and mitigating climate change. In this effort to reduce carbon emissions, the agricultural knowledge and innovation ecosystem—embedded in the very foundations of the Common Agricultural Policy—must be inclusive and open to all actors.

It is encouraging to note that the Climate Farm Demo (CFD) project is a shining example of this ecosystem in action at both the national and EU levels. The exchange of knowledge at all levels and the application of innovative techniques in agriculture represent the starting point in the fight against climate change.

Agriculture is one of the most vulnerable sectors affected by climate change. Therefore, agricultural producers who recognize the impact of climate change on agricultural production—as well as the need to adapt their practices and implement climate-smart approaches—have joined the CFD project.

It is important to present to farmers engaged in arable production the structure of sowing on farms, the methods of tillage, and whether (and which) cover crops are sown (winter or spring). As integral stakeholders in the AKIS system, producers and distributors of seeds—particularly those offering leguminous seeds and seed mixtures of different botanical species for various purposes—must be involved in agricultural adaptation to climate change.

It is also important to demonstrate to farmers the variety of winter cover crops, such as mixtures of winter vetch, winter broad beans, and black beans, as well as broad bean crops intended for processing. It is essential to show the nodules on legume roots and to emphasize the benefits of incorporating legumes into crop rotation.

However, it must also be emphasized that sowing cover crops involves several different soil maintenance measures, supported by vegetation on the land. These measures aim to maintain or increase soil organic matter, improve the physical properties of the soil (including structure and water air balance), accumulate nitrogen in the soil through legume growth, enhance soil microbiological activity, and control weeds through biological means—in general, to increase soil fertility.

Additionally, cover crops serve the function of “soil cover,” intended to prevent erosion (by water and/or wind) and nutrient leaching, particularly nitrates, thus reducing the risk of groundwater pollution.

Digitalization and Precision Livestock Farming: What are the Benefits for Reducing the Environmental Impact in Dairy Farms

Italy

Mediterranean area

Benefits of the practice

- Animal welfare

- Farm production efficiency

- Environmental sustainability

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

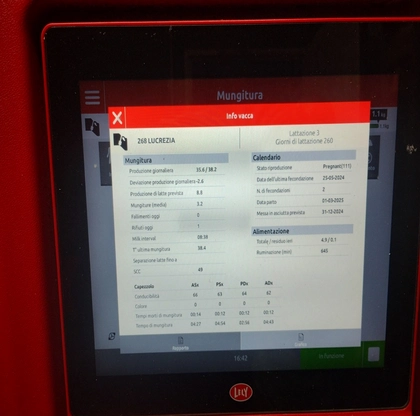

Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) represents a new opportunity for dairy farms to address market challenges by improving the efficiency of company production, enhancing both animal welfare, thanks to the ability to monitor and manage the individual and not just the group, and the sustainability of production. PLF is the use of technologies to measure physiological, behavioral, productive and reproductive indicators on individual animals, with the aim of improving management strategies and the performance of the subjects raised. The application of these technologies allows the collection and management of a large amount of information, which, if managed optimally, can be of great help in managing and controlling the herd in an effective and profitable way.

With PLF, various parameters can be monitored to evaluate the state of health, animal welfare, productive and reproductive performance of the farm, which are closely related to the environmental impact. It has been shown that the reduction of mastitis resulting from the timely recognition of the pathology can lead to a 2.5% decrease in global warming potential as well as a reduction in the use of antibiotics. (See Tullo et. Al, 2019) Good management of the reproductive status of animals can contribute to reducing environmental impact. In fact, by maintaining fertility at the highest level, it is believed possible to reduce the farm’s GHG emissions by more than 20%. (See Tullo et. Al, 2019) The PLF, if used well, allows the breeder to make some decisions more promptly, thus improving the productivity and profitability of his farm. To make the most of the information obtained with these technologies and interpret them correctly, it is essential that they are integrated with computerized information systems capable of managing and processing the enormous “amount” of data produced and that there are qualified personnel in the stable who knows how to interpret them.

La zootecnia di precisione (Precision Livestock Farming, PLF), rappresenta la nuova opportunità per gli allevamenti da latte per affrontare le sfide dei mercati attraverso un miglioramento dell’efficienza di produzione aziendale, valorizzando sia il benessere animale, grazie alla possibilità di monitorare e gestire il soggetto e non solo il gruppo, sia la sostenibilità delle produzioni. La PLF è l’utilizzo di tecnologie per misurare indicatori fisiologici, comportamentali, produttivi e riproduttivi sui singoli animali, con l’obiettivo di migliorare le strategie gestionali e le performance dei soggetti allevati. L’applicazione di queste tecnologie permette il rilievo e la gestione di un grande numero di informazioni, che, se gestito in maniera ottimale, può risultare di grande aiuto per gestire e controllare la mandria in maniera efficace e remunerativa. Con la PLF si possono monitorare diversi parametri con cui si valuta lo stato di salute, il benessere animale, le performance produttive e riproduttive dell’allevamento, che sono strettamente correlati all’impatto ambientale. E’ stato dimostrato che la riduzione delle mastiti derivante dal riconoscimento tempestivo della patologia può comportare una diminuzione del 2,5% del potenziale di riscaldamento globale oltre che ad una riduzione nell’utilizzo degli antibiotici. Una buona gestione dello stato riproduttivo degli animali può contribuire alla riduzione dell’impatto ambientale. Infatti, mantenendo la fertilità al massimo livello, si ritiene possibile ridurre l’emissione di gas serra aziendale per più del 20%. La PLF, se ben utilizzata, consente all’allevatore di prendere con più tempestività alcune decisioni, migliorando in questo modo la produttività e la redditività del proprio allevamento. Per sfruttare al massimo le informazioni ottenute con queste tecnologie ed interpretarle in maniera corretta, è fondamentale che queste siano integrate con sistemi informativi computerizzati in grado di gestire ed elaborare l’enorme “mole” di dati prodotti e che ci sia in stalla del personale qualificato che li sappia interpretare.

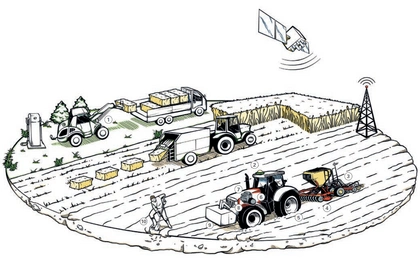

Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) represents a valuable opportunity for dairy farms to respond to market challenges by increasing production efficiency, enhancing animal welfare—thanks to the ability to monitor and manage animals individually rather than as a group—and improving the overall sustainability of production.

PLF refers to the application of engineering principles and techniques in livestock farming to automatically monitor, model, and manage animal production. Through these technologies, it is possible to measure physiological, behavioral, productive, and reproductive indicators at the individual animal level. The goal is to improve management strategies and animal performance, making livestock farms more sustainable economically, environmentally, and socially.

The use of PLF technologies enables the collection and management of large volumes of data, which—if handled effectively—can significantly improve herd control in a cost-efficient and productive manner. Animal scan be identified and tracked via GPS and image analyzers, which are useful for observing animal behavior and conducting automated assessments of body weight, Body Condition Score, and foot lesions. Realtime monitoring tools such as activometers, collars, body temperature sensors, milking robots, and devices based on near-infrared spectroscopy(NIRS) provide valuable information on health status, welfare, and productive and reproductive performance, all of which are closely linked to environmental impacts and milk quality.

Studies have shown that timely identification and management of mastitis through PLF technologies can lead to a 2.5% reduction in global warming potential, in addition to decreased antibiotic usage. Proper reproductive management can also reduce environmental impacts; maintaining optimal fertility levels may decrease greenhouse gas emissions from the farm by more than 20%.

Furthermore, monitoring the chemical composition of animal diets using precision feeding technologies can boost herd productivity while reducing enteric methane emissions and nitrogen excretion, thereby lowering emissions from livestock waste.

When effectively implemented, PLF empowers farmers to make more timely and informed decisions, improving productivity, profitability, and veterinary drug use on the farm. However, to fully capitalize on the potential of these technologies, it is crucial to integrate them with computerized information systems capable of processing the vast amount of data generated. Equally important is the presence of qualified personnel on-site who can correctly interpret and act on this information.

Subsoiling

Slovenia

Marine West Coast, Warm Summer

Benefits of the practice

- Deep soil loosening,

- Soil drainage,

- Soil aeration and thus stimulating soil microbiological activity.

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

The main purpose of deep tillage is to break through the silt, which is created by many years of tillage at the same depth. Silt is a compacted, impenetrable layer of soil that stops air circulation and, above all, water draining into the depths. The positive effects of such deep tillage are soil drainage, soil aeration, and thus stimulating soil microbiological activity. When we loosen the soil, we achieve that the soil is less compacted and enable easier root growth into deeper layers of the soil. It is known that if the roots cannot break through the silt, they redirect their growth horizontally and continue to grow. If we have a dry period, this is very bad, because they do not reach the deeper layers of the soil, which still retain a certain amount of water, and therefore suffer drought stress more quickly. In periods of high rainfall, silt also causes water to stagnate on the surface of the soil. With deep tillage, we can alleviate this stagnation, because we loosen the soil deeply, break through the silt, and therefore the water drains faster. Also, certain versions of deep tillers have a drainage cone installed behind the head of the tiller, which creates a natural tube in the depth, which serves to drain water from the surface into the nearest drainage ditches. This measure is much more effective if we start with the processing itself next to the water drainage ditch and then process inland. This directs the flow of water into the ditch. When we deeply loosen the soil, we bring air into the depth of the soil. Air allows faster reproduction and activity of microorganisms in the soil. When we have good activity of microorganisms, we also have more nutrients available to plants.

Glavni namen globinskega podrahljavanja je prebiti plazino, ki se ustvari z dolgoletno obdelavo tal na isti globini. Plazina je strnjena, neprebojna plast zemlje, ki ustavlja kroženje zraka, predvsem pa odvajanje vode v globino. Pozitivni učinki takšne obdelave tal so globinsko podrahljanje tal, drenažiranje tal, prezračevanje tal ter s tem spodbujanje mikrobiološke aktivnosti tal. Ko tla prerahljamo dosežemo to, da so tla manj zbita in omogočimo lažjo rast korenin v globlje plasti zemlje. Znano je, da korenine če ne morejo prebiti plazine, preusmerijo rast vodoravno in rastejo tako naprej. V kolikor imamo sušno obdobje je to zelo slabo, saj ne dosežejo globljih plasti zemlje, ki še zadržujejo določeno količino vode, zato hitreje utrpijo sušni stres. V obdobjih, ko imamo veliko padavin, prihaja zaradi plazine tudi do zastajanja vode na površini zemlje. S globinskim podrahljavanjem lahko to zastajanje omilimo, saj prerahljamo tla v globino, prebijemo plazino, zato voda hitreje odteče. Prav tako imajo določene izvedbe globinskih podrahljačev nameščene za glavo nogače drenažni kegelj, ki naredi v globini naravno cev, ki služi odtekanju vode iz površine v najbližje jarke za odvodnjavanje. Ta ukrep je veliko bolj učinkovit, če začnemo s samo obdelavo ob jarku za odvajanje vode in nato obdelujemo v notranjost površine. S tem usmerimo tok vode v jarek. Ko tla globinsko podrahljamo, spravimo zrak v globino tal. Zrak omogoča hitrejše razmnoževanje in delovanje mikroorganizmov v zemlji. Kadar imamo dobro delovanje mikroorganizmov imamo tudi več hranil, ki so na voljo rastlinam.

In agriculture, we know several methods of soil cultivation: from conventional cultivation with a plow, through minimal cultivation with tools that only work the soil shallowly, to direct sowing or no-till cultivation. All these treatments have in common that they do not work deeper than 25 30 cm into the very depth of the soil. When we work deeper, we call this subsoiling (deep soil loosening). In this mechanical work, we intervene in the soil up to a depth of 120 cm.

The main purpose of this measure is to break through the silt, which is created by many years of soil cultivation at the same depth. Silt is a compacted, impenetrable layer of soil that stops air circulation, and above all, the drainage of water into the depth. The positive effects of such soil cultivation are deep soil loosening, soil drainage, soil aeration and thus stimulating soil microbiological activity. When we loosen the soil, we achieve that the soil is less compacted and enable easier root growth in the deeper layers of the soil. It is known that if the roots cannot break through the soil, they redirect their growth horizontally and continue to grow. If we have a dry period, this is very bad, because they do not reach the deeper layers of the soil, which still retain a certain amount of water, and therefore suffer drought stress more quickly. In periods when we have a lot of precipitation, soil also causes water to stagnate on the surface of the soil. With deep loosening, we can alleviate this stagnation, because we loosen the soil deeply, break through the soil, so the water drains faster. Also, certain versions of deep looseners have a drainage cone installed behind the head of the legs, which creates a natural pipe in the depth, which serves to drain water from the surface into the nearest drainage ditches. This measure is much more effective if we start with the processing only next to the water drainage ditch and then process into the interior of the surface. This directs the flow of water into the ditch. When we deeply loosen the soil, we get air into the depth of the soil. Air allows for faster reproduction and activity of microorganisms in the soil. When microorganisms are functioning well, we also have more nutrients available to plants.

Farmers use deep loosening to the greatest extent in the summer months.

After harvesting cereals and oil seed rape and before sowing follow-up crops is the most suitable time for this task. The soil is also dry enough at this time to carry out this measure. If we have a crop present throughout the summer and have problems with water retention, deep loosening can also be carried out before sowing this crop. Of course, the soil must be suitably dry and walkable.

At the Agricultural Day, which took place on August 2, 2024 in Bohova, various subsoilers were presented. Subsoilers suitable for smaller tractors(70-100 HP) and those requiring much greater pulling power (250+ HP) were demonstrated. The differences were also in the shape of the tines and their effect on the soil. After the presentation of each subsoiler, we dug a hole so that we could closely observe the effects on the soil at depth. The purpose of the event was to show farmers and the general public the usefulness of subsoilers and to help them make decisions regarding their purchase and use.

Sowing Stubble Crops

Slovenia

Marine West Coast, Warm Summer

Benefits of the practice

- Improve soil fertility,

- Improve crop rotation,

- Avoid soil structure deterioration due to heat and summer storms in the summer.

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Stubble crops are sown after the harvest of cereals, early potatoes, and catch crops. Sowing stubble crops in the crop rotation has several advantages: it improves the rotation, prevents the deterioration of soil structure in the summer due to heat and summer storms, produces additional fodder for livestock, and prevents the spread of diseases and pests.

By sowing stubble crops, we reduce weed infestation, improve soil aeration and the humus balance, lessen the negative effects of rain, sun, and wind on soil structure, prevent the leaching of nutrients (especially nitrogen) into groundwater, improve the farm’s feed balance, provide bees with rich pasture in the autumn, and benefit from biofumigation, which has a suppressive effect on certain soil pests. Mixtures of several stubble crops also contribute to greater biodiversity.

Stubble crops are important because they enhance the visual appearance of the landscape. They can be sown without ploughing, using only shallow surface tillage. Stubble crops are grown for human consumption, animal feed, and green cover. Their importance is even greater in areas where manure is not ploughed in.

For human consumption, buckwheat, millet, stubble turnip, or beetroot are sown. For animal feed, the most sown crops include multi-flowered ryegrass, red clover, vetch, black clover, fodder rape, alfalfa, and clover-grass mixtures. For green cover, oil radish, white mustard, sunflowers, phacelia, and plant mixtures are used.

Stubble crops can be either winter or non-winter varieties.

Strniščne dosevke sejemo po spravilu žit, zgodnjega krompirja in vmesnih posevkov. Setev strniščnih dosevkov ima v njivskem kolobarju več prednosti: izboljšamo kolobar, v poletnem času se izognemo propadanju strukture tal zaradi vročine in poletnih neviht, pridelamo dodatno krmo za živino in preprečujemo razmnoževanje bolezni in škodljivcev. S setvijo dosevkov zmanjšamo zapleveljenost , izboljšamo zračnost tal ter bilanco humusa, zmanjšamo negativne vplive dežja, sonca in vetra na strukturo tal, preprečujemo izpiranje hranil (dušika) v podtalnico, izboljšamo krmno bilanco na kmetiji, čebelam zagotavljamo bogato pašo v jesenskem času, z biofumigacijo negativno vplivamo na nekatere talne škodljivce. Z mešanicami večih dosevkov pripomoremo k večji biodiverziteti. Strniščni dosevki so pomembni, ker polepšajo tudi izgled krajine. Setev strniščnih posevkov lahko opravimo brez oranja, samo s plitvo površinsko obdelavo tal. Strniščne dosevke sejemo za prehrano ljudi, za krmo živali in za zeleni podor. Pomen setve strniščnih dosevkov je še večji na površinah na katerih ne zaoravamo hlevskega gnoja.

Za človeško prehrano sejemo ajdo, proso, strniščno repo ali rdečo peso, za prehrano živali najpogosteje sejemo mnogocvetno ljulko, inkarnatko, grašljinko, črno deteljo, krmno ogrščico, lucerno in deteljno travno mešanico, za zeleni podor pa oljno redkev, belo gorjušico, sončnice, facelijo in mešanice rastlin. Strniščni posevki so lahko prezimni ali neprezimni.

Sowing stubble crops is an environmentally friendly and effective way to improve soil fertility. It provides year-round soil coverage and is a highly recommended measure from a professional point of view. Given this year’s(2025) weather conditions, when there is still enough moisture in the soil, we can recommend sowing the stubble as soon as possible.

For human consumption, we sow buckwheat, millet, stubble turnip or beetroot, for animal consumption we most often sow multi-flowered ryegrass, red clover, vetch, black clover, fodder rape, alfalfa and clover grass mixture, and for green fodder we sow oil radish, white mustard, sunflowers, phacelia and plant mixtures. Stubble crops can be winter or non-winter crops. (See Table 1 and Table 2)

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Results of the stubble yield experiment (See more information in Table 3):

• Fertilization: 30m3 of cattle manure per ha

• Cultivation: – hoeing to a depth of 15 cm 8.8.2020

o harrow 9.8.2020

• Sowing: 10. 8. 2020

• Harvest of the experiment and weighing: 3. 11. 2020

• Mulched: 12.11.2020

• Ploughed: 15.11.2020

Sowing is mostly done with grain seeders or mineral fertilizer spreaders, but it can also be done manually. After sowing, we can also roll the seeds to ensure more even and faster emergence. If your main crop (e.g. pumpkins) has failed and was sprayed with soil herbicides, we advise you to call us for detailed instructions on how to sow follow-up crops in such a case.

How Soil Cover and Reduced Tillage Enhance the Stability and Resilience of Agriculture to Extreme Weather Events

Switzerland

Temperate Climatic

Benefits of the practice

- Maintaining soil health

- Increase resilience

- Emission mitigation

Thematic Area(s)

The Climate Farm Demo event in Bavois, Switzerland, in October 2024 focused on educating and training agricultural professionals about the essential role of cover crops as well as methods like direct seeding, in addressing the challenges posed by climate change.

Research presented at the event showed that soil covered by plants can absorb rainwater more effectively, reduce erosion, and heat up less in summer. In contrast, uncovered soils are vulnerable to water and nutrient losses, as well as soil erosion. An aggregate stability test conducted on-site illustrated how soil stability is affected by management practices and how plant cover can improve soil stability.

Individuals from agricultural practice and advisory can leverage these insights by integrating strategies for implementing cover crops and reduced tillage into their farming practices. These methods improve soil quality and fertility, contributing to long-term yield stability and increases.

At the end of the event, Hanspeter Liniger (University of Bern) shared findings from the “Hot earth is not cool” project, highlighting how uncovered soils are highly vulnerable to erosion, runoff, and heat stress. He explained that covered soils absorb and store rainwater better, protecting against erosion and drought. Rain simulator studies show that up to 50% of heavy rainfall runs off uncovered soils, causing major losses of water, soil, and nutrients. In contrast, soils under permanent pasture or cover crops with no-till practices showed minimal runoff and erosion. Uncovered soils can heat up to over 60°C in summer, harming soil life. Mulch can lower topsoil temperatures by 15–20°C, while living plant covers are even more effective and help stabilize soil structure. Frequent ploughing disrupts roots and soil microbes, weakens soil stability and increases erosion risks.

Die Climate Farm Demo Veranstaltung in Bavois, Schweiz, im Oktober 2024 legte den Schwerpunkt auf die Aufklärung und Weiterbildung von Fachleuten in der Landwirtschaft über die wesentliche Rolle von Bodenbedeckungspflanzen, wie Gründüngungen und Zwischenfrüchten und Methoden wie der Direktsaat, zur Bewältigung der Herausforderungen des Klimawandels.

An der Veranstaltung präsentierte Forschungsergebnisse zeigten auf, dass durch Pflanzen bedeckte Böden Regenwasser effektiver aufnehmen, Erosion reduzieren und sich im Sommer weniger stark erhitzen. Unbedeckte Böden hingegen sind anfällig für Wasser- und Nährstoffverluste sowie Bodenerosion. Ein vor Ort durchgeführter Aggregatsstabilitätstest illustrierte, wie die Bodenstabilität durch die Bodenbewirtschaftungsart beeinflusst wird, und wie eine Bodenbedeckung durch Pflanzen die Stabilität des Bodens verbessert.

Personen aus der landwirtschaftlichen Praxis und Beratung können die gewonnenen Erkenntnisse nutzen, indem sie Strategien für die Implementierung der Bodenbedeckung durch Pflanzen und der reduzierten Bodenbearbeitung in ihren Anbau integrieren. Diese Methoden verbessern die Bodenqualität und -fruchtbarkeit und tragen dazu bei, die Erträge langfristig zu stabilisieren und zu steigern.

Zum Abschluss der Veranstaltung stellte Hanspeter Liniger (Universität Bern) die Ergebnisse des Projekts „Hot earth is not cool“ vor und zeigte auf, dass unbedeckte Böden sehr anfällig für Erosion, Abfluss und Hitzestress sind. Er erläuterte, dass bedeckte Böden Regenwasser besser aufnehmen und speichern und so vor Erosion und Trockenheit schützen. Studien mit Regensimulatoren zeigen, dass bis zu 50 % der starken Regenfälle von unbedeckten Böden abfließen und große Verluste an Wasser, Boden und Nährstoffen verursachen. Im Gegensatz dazu wiesen Böden unter Dauergrünland oder Deckfrüchten mit Direktsaatverfahren nur minimale Abfluss- und Erosionswerte auf. Unbedeckte Böden können sich im Sommer auf über 60 °C aufheizen und das Bodenleben schädigen. Mulch kann die Oberbodentemperaturen um 15-20 °C senken, während lebende Pflanzendecken noch wirksamer sind und zur Stabilisierung der Bodenstruktur beitragen. Häufiges Pflügen stört Wurzeln und Bodenmikroben, schwächt die Bodenstabilität und erhöht das Erosionsrisiko.

As a result of climate change, agricultural soils are increasingly exposed to extreme weather conditions such as heatwaves, droughts and heavy rainfall.

These changes threaten soil fertility and therefore also agricultural yields.

At the well-attended Climate Farm Demo event on 9 October 2024 in BavoisVD, the crucial role of soil cover was illustrated in a practice-oriented event.

After a welcome to the attendees by a consultant from the Prométerre association, the Climate Farm Demo farmer Thierry Salzmann shared his experiences with cover cropping and reduced tillage. He explained how he practically implements techniques such as no-till farming on his farm and the advantages he sees in it. Afterwards, the agricultural experts had the opportunity to experience at various stations how soil cover has a positive effect on various soil properties, such as soil structure, nutrient availability, biodiversity and soil organisms.

Towards the end of the event, Hanspeter Liniger from the University of Bern presented important research findings on the topic of soil protection. As part of the ‘Hot earth is not cool’ project, Liniger explained the problems that uncovered soils can lead to and which agricultural practices can help to protect soils from extreme weather events and maintain soil fertility in the long term:

• Covered soils can absorb and store rainwater more effectively and are therefore better protected against erosion and drought. Uncovered and freshly tilled soils, on the other hand, are particularly susceptible to surface runoff and erosion. Studies with rain simulators show that as much as half of the simulated heavy rainfall runs off on uncovered soil, resulting in substantial losses of water, soil and nutrients.

Conversely, soils cultivated with permanent pasture or protected by a green cover crop sown using no-till practices markedly diminished surface runoff and minimized erosion to nearly zero.

• Uncovered soils can heat up to over 60°C in summer, stressing soil life.

Mulch cover can lower the top soil temperature by 15 to 20 °C. A living soil cover is even more effective and also improves the stability of the soil structure.

• Roots and soil microbes are crucial for soil stability. Frequent ploughing disturbs soil life and leads to unstable soils, which in turn favours runoff and erosion.

As a conclusion, the investigations of Hanspeter Liniger und Jovana Askrabic in summer 2023 and 2024 showed that protecting soils from heat stress, surface runoff and erosion is crucial for resilient agriculture. Adapted cultivation methods can make soils more resistant to climatic extremes, secure yields and also protect the environment in the long term.

The full article on Liniger and Askrabic’s research can be read here

Optimisation of Irrigation in Olive Cultivation Using Sensors, Drip Irrigation and Monitoring of Climatic Conditions

Greece

Mediterranean

Benefits of the practice

- Irrigation optimisation to reduce water loss

- Increasing production even in periods of severe drought

Production system(s)

Thematic Area(s)

Optimising irrigation in olive groves is critical for increasing efficiency and ensuring sustainability, especially in regions with limited water resources. Proper irrigation management reduces water waste and supports higher olive yields.